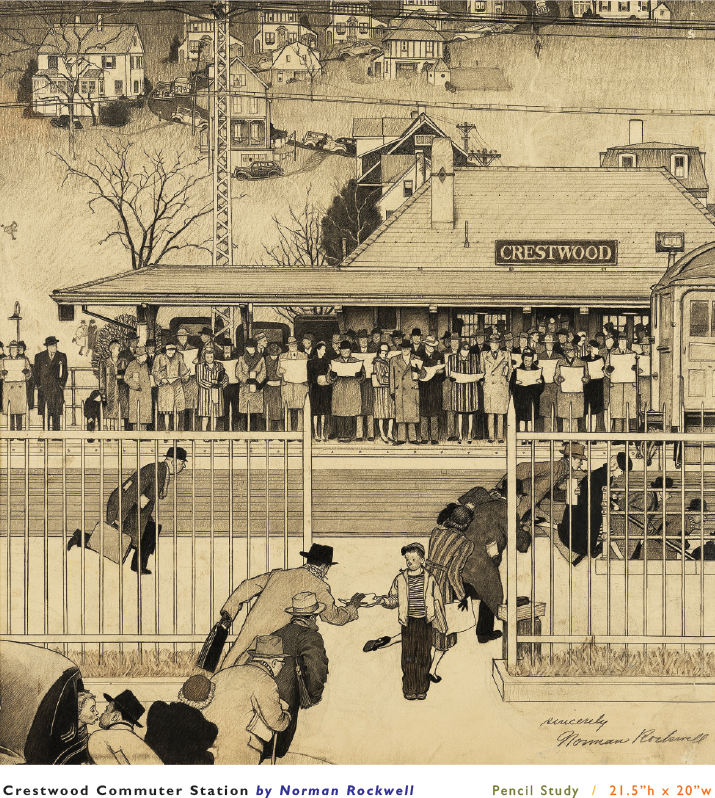

One of Norman Rockwell’s most beloved works, “Crestwood Commuter Station,” is not one of the master American illustrator’s usual close-up character studies. Instead, Rockwell’s artist’s-eye “camera” pulls back to reveal a wide shot of the hustle and bustle of a commuter train station in the mid-1940s.

In the illustration, men in hats and women in heels rush to the underpass and stand crowded before the station, reading newspapers as they wait for their train. A woman in curlers leans out of a car window to kiss her husband goodbye as she sees him off to work. Front and center, a red-nosed newsboy vends papers to the passing throng. The work appeared on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post’s November 16, 1946 issue and immediately became one of the illustrator’s classic, enduring images.

The Hilbert Museum of California Art has acquired a very finished study for this work, from the pencil of Rockwell, going on display in the exhibition “Sincerely, Norman Rockwell: Celebrating a New Acquisition,” opening February 2.

“The finished study offers a wonderful opportunity for museum guests to get a glimpse of the genius mind of Rockwell at work,” says Hilbert Museum Director Mary Platt, curator of the exhibition. “The piece provides a glimpse of a lost Americana of the mid-last-century and features Rockwellian slices of life, engaging portraits and caricatures, with even a bit of landscape in the background. It’s so packed with imagery that whenever you look at it, you always see something new.”

“The Hilbert Collection’s newly acquired piece is likely what is called a ‘comp,’ or comprehensive drawing for the finished piece,” says illustration expert Gordon McClelland, who has curated several exhibitions for the Hilbert Museum. The finished work, as seen on the magazine cover, is part of a private collection and has been shown at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Both the Hilbert study and the finished piece appear in Norman Rockwell: A Definitive Catalogue by Laurie Norton Moffatt.

“Crestwood Commuter Station” was Rockwell’s 242nd out of his 322 paintings published on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post, one of the most popular of the mid-20th-century mass-audience magazines. His career with the Post spanned 47 years, from his first cover in 1916 to his last, a portrait of John F. Kennedy, in 1963.

Rockwell is one of America’s best-known artists. “If you ask someone to name an American illustrator, often the only one they can think of is Norman Rockwell,” says Platt. “Of all the great ones, he’s the only household name.” Part of that is due to the clever way the Rockwell organization has marketed his works, with reproductions still churned out on coffee mugs, umbrellas, t-shirts, puzzles and other bric-a-brac. But part of it, too, is his deft hand, effortless ease of color and line, and the genuine joy he takes in his subject matter.”

While some prominent art critics turned up their noses at Rockwell during his lifetime, calling his work sentimental and saccharine, recent articles and exhibitions have taken a more admiring look at this iconic illustrator, praising him for his immense skill as a figurative and narrative painter and for his keen social observation. Many of his pieces have hit auction records, such as “Saying Grace,” selling for $46 million in 2013. His paintings are regularly snapped up at lofty prices by celebrity collectors like George Lucas and Steven Spielberg.

Born in New York City, Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) began his art studies at the National Academy of Design and later attended the Art Students League. Like his contemporary Walt Disney, Rockwell’s particular genius was in portraying a sincere and heartfelt appreciation for America and the American way of life. “Without thinking too much about it in specific terms, I was showing the America I knew and observed to others who may not have noticed,” Rockwell said of his work.

Rockwell painted his first commissioned pieces, a set of Christmas cards, when he was just 16, and became art director of Boy’s Life while still in his teens. At 21, he moved to New Rochelle, New York, where a number of famous American illustrators, including J.C. and Frank Leyendecker, had studios. After painting covers for several other magazines, Rockwell received his first commission for a Saturday Evening Post cover in 1916, at the age of 22. Rockwell married, divorced and married again, and moved his little family to Arlington, Vermont in 1939. The 1930s and 1940s are considered to be Rockwell’s most fruitful artistic years, as his themes shifted to small-town American life and its characters.

In 1943, Rockwell, inspired by President Franklin Roosevelt’s address to Congress, painted “The Four Freedoms.” “Freedom from Want” (the famous “grandma serving the turkey” painting), “Freedom of Speech,” “Freedom to Worship” and “Freedom from Fear” were published in successive Saturday Evening Post issues. The illustrations became enormously popular and toured the U.S. in an exhibition sponsored by the Post and the U.S. Treasury Department, raising more than $130 million for the war effort.

The Rockwells next moved to Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where he continued his prolific production of illustrations. In 1963, he ended his nearly five-decade association with the Saturday Evening Post and went to work for Look magazine, where the themes of his works spanned issues ranging from the war on poverty to space exploration. In the 1970s, he established a trust to preserve his artistic legacy and founded the society that would later become the Norman Rockwell Museum. He passed away peacefully at his home in Stockbridge in November 1978, at the age of 84.

Hilbert Museum Founder and Chapman University Trustee Mark Hilbert, who acquired “Crestwood Commuter Station” for the Hilbert Collection, says that one of the joys of looking at the piece is seeing all the different faces—including, he believes, some famous ones. “There’s a man in a bowler hat, carrying two briefcases, who looks exactly like famous movie director Alfred Hitchcock. And there’s another figure that clearly is a self-portrait of Rockwell himself, right down to the trademark pipe in his mouth.” Hilbert hopes museum visitors pick out even more hidden celebrity portraits in the drawing.

Crestwood Station is a real place. Located in the village of Tuckahoe, New York, it’s the first stop out of New York City on the Metro-North Railroad’s Harlem Line. Its name comes from the adjoining community of Crestwood, Yonkers, and it’s still a busy place. Visitors to today’s Crestwood Station, though, would be hard-pressed to recognize the lively, quaint little station in Rockwell’s 1946 portrayal. Recent changes have included a towering, glass-enclosed overpass where the new ticket office is located, while the old station remains boarded-up by the tracks.

But through the lens of Norman Rockwell’s sharply focused, amber-hued time machine, you can still see the station as it once was: standing proud in the heart of a small-town village, a waypoint on the journey from here to there, populated by a gathering of uniquely American figures in a uniquely American hurry, frozen in mid-bustle on a crisp autumn morning in 1946.

- - - -

“Sincerely, Norman Rockwell: Celebrating a New Acquisition” opens at the Hilbert Museum of California Art at Chapman University on Saturday, February 2, with an Opening Reception from 6 to 8 pm that evening. The exhibition runs through October 2019. Admission to the Hilbert Museum is free, and there is free parking in front of the museum with a permit obtained inside. 167 North Atchison St., 714-516-5880; www.hilbertmuseum.org.