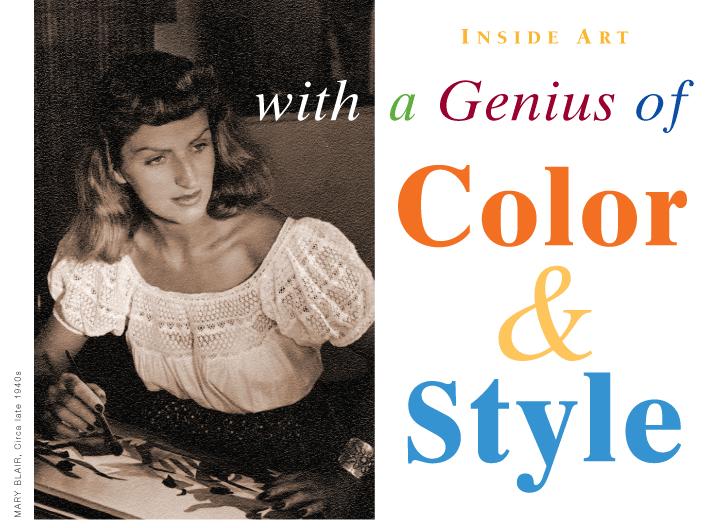

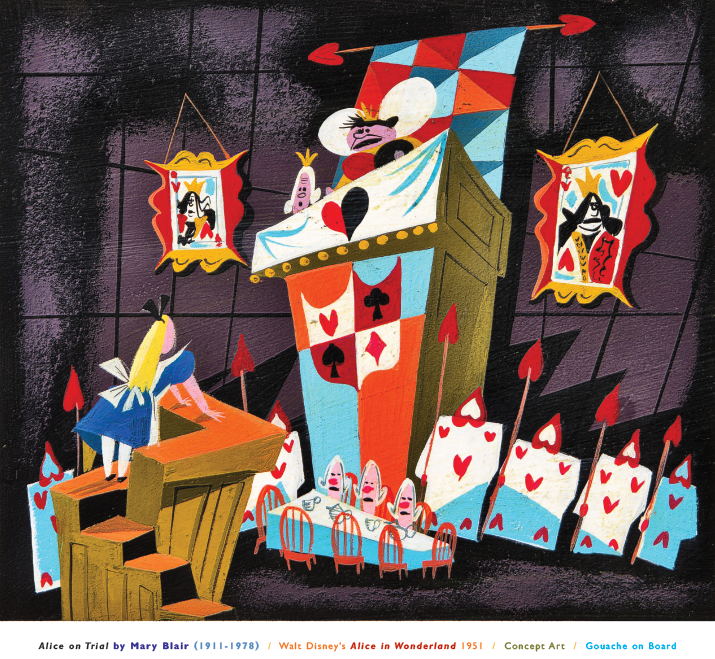

Mary Blair (1911-1978) is known worldwide to Disney fans as the matchless designer, illustrator and colorist, who set the tone for such iconic animated films of the wartime era through the midcentury as Dumbo (1941), Saludos Amigos (1942), The Three Caballeros (1945), Song of the South (1946), Make Mine Music (1946), Melody Time (1948), So Dear to My Heart (1948), Cinderella (1950), Alice in Wonderland (1951) and Peter Pan (1953).

Blair is the subject of a fascinating current exhibition at the Hilbert Museum of California Art at Chapman University. “The Magic and Flair of Mary Blair” includes more than 20 of her concept paintings for Walt Disney Studios and the Imagineering division.

As a fine artist, Blair was a member of the California Water Color Society early in her artistic life. The president of the Society, starting in 1935, was Lee Blair, who had wed Mary in 1934, and was also a well-respected Disney artist. Mary and Lee exhibited their paintings together in solo and group shows throughout the 1930s.

Her art had such an immediate and innate joy, conveying so much emotion in seemingly “simple” designs, that she was revered by Walt Disney himself as a fellow genius. “She could draw like nobody else and paint like nobody else,” said Frank Thomas, one of the group of Disney animators known as the “Nine Old Men.”

After Blair joined Disney Studios in 1940, her art began to catch Walt’s eye. In 1941, she and husband Lee accompanied Walt Disney, his wife Lillian, and a small group of other Disney artists on a three-month “artistic ambassador” tour of South America sponsored by the U.S. government, aimed at increasing good will between the United States and its Western Hemisphere neighbors while Europe was at war. The artists sketched and painted continuously along the way as they traveled through Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, Argentina, Bolivia and other countries.

That trip opened Blair’s eyes to a much wider world of brilliant color and creative line, and her paintings became brighter, livelier and more stylized. Walt loved her work, and Blair became one of the few women artists who broke the glass ceiling at Disney in that era, rising to become the most influential concept artist at the studio. By and large, though, her work was too individualistic to be translated fully to the screen, and the animators would revert back to the tried-and-true Disney style of rounded characters and realistic backgrounds. Both Walt and Mary were often frustrated by this dichotomy of styles and the inability to convey her unique vision from her paintings to the screen.

Disney animator Marc Davis, another of the “Nine Old Men,” said of Blair’s work during this period, “All the men who were at Disney, their design was based on perspective. But Mary did things on marvelous flat planes. Walt appreciated this…but he was never able to instruct the men on how to use [her work]. It was tragic, because she did things that were so marvelous and never got on the screen.”

Partially because of that— and partially because Blair’s talents were simply too remarkable to be contained even by Disney—in 1953 she amicably left the studio to forge new career successes. As an independent illustrator and designer, she created many memorable advertising illustrations, murals, tiles, fabric and fashion designs, television commercials and stage productions. Her illustrations for the popular Little Golden Books series are still in print today and are treasured by children around the world.

Blair’s style marvelously evoked the spirit of childhood, much in the same way that Picasso’s later works would. (As Picasso once said, “It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.”) “Somehow, Mary Blair conveys some of the feeling of what it is like to be the child doing the thing she pictures. Or to be the horse, or the owl, or to be the flower, or blade of grass, or cloud in the sky,” commented Wilfred Jackson, the Disney feature animation director best known for his work on Mickey Mouse cartoons and on “Fantasia.”

Blair and Walt Disney remained lifelong friends, so he called on her again in 1963, opening up a whole new phase of her creative life. Walt had been asked to design several pavilions for the 1964 New York World’s Fair, including one for Pepsi that honored UNICEF, the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, and which showcased the theme of “children of the world.”

Blair’s innovative design of the exterior and interior of that ride—including all the audio-animatronic children inside it—was such a hit that “It’s a Small World” was duplicated at Disneyland in Anaheim in 1966, and has been replicated at Disney World and Disney parks around the globe.

Walt Disney’s death in 1966 devastated Blair, but she went on to create two huge murals for Tomorrowland (1967) at Disney-land (now encased inside a wall, but still preserved), and a monumental ceramic mural inside the Contemporary Resort Hotel at Walt Disney World in Florida (1971), which can still be viewed.

Blair died on July 26, 1978, at the age of just 66, still creating her inimitable art to the very end. Her posthumous awards include being named a Disney Legend in 1991, and receiving the prestigious Winsor McCay Award from the International Animated Film Society in 1996. Her 100th birthday was celebrated in 2011 with a Google Doodle. Blair’s legend and artistry live on—and more than 20 of her works, ranging from her Disney movie art to her designs for “It’s a Small World,” can be seen in the Hilbert Museum exhibition.

Animation director John Canemaker, who has written two books about Blair’s life and art, sums up the legacy of this remarkable creative mind: “Mary Blair’s fearless artistic sensibilities and magical paintbrush created an intense reality all her own. No matter the subject matter or medium, the feeling of joy that she took in her limitless creativity is palpable, and it continues to communicate and fascinate viewers of all ages all over the world.”

- - - -

“The Magic and Flair of Mary Blair” exhibition is on view at the Hilbert Museum of California Art through October 19, 2019. The Hilbert Museum is located at 167 North Atchison St. in Orange, across from the Metrolink station. Hours are Tuesday-Saturday, 11am to 5pm. Admission is free. Free parking in front of the museum with a permit obtained at the front desk, or plenty of free parking now available just one block east of the museum in the new Old Towne West Metrolink Parking Structure at 130 North Lemon St. For more information, the public can call 714-516-5880 or visit www.hilbertmuseum.org.