Back in the 1880s, if you were a middle class or wealthy person on the East Coast or in the Midwestern United States, you were probably a new customer for a sweet, golden bounty suddenly flowing by train from California: citrus fruits.

With the construction of the Southern Pacific and Santa Fe railroads in the late 1870s and early 1880s, combined with the development of new refrigerated train cars, fruit growers on the West Coast could send their produce east without fear of spoilage. Oranges had been cultivated in California since the late 1700s, brought in from Mexico, but in those early years the fruits were grown mainly for local consumption.

With the new shipping possibilities, the Southern California growers were faced with challenges: how to pack, identify and advertise their products to people in the rest of the country. One handy solution was to design brightly colored, attractive paper labels for the wooden crates the fruits were shipped in.

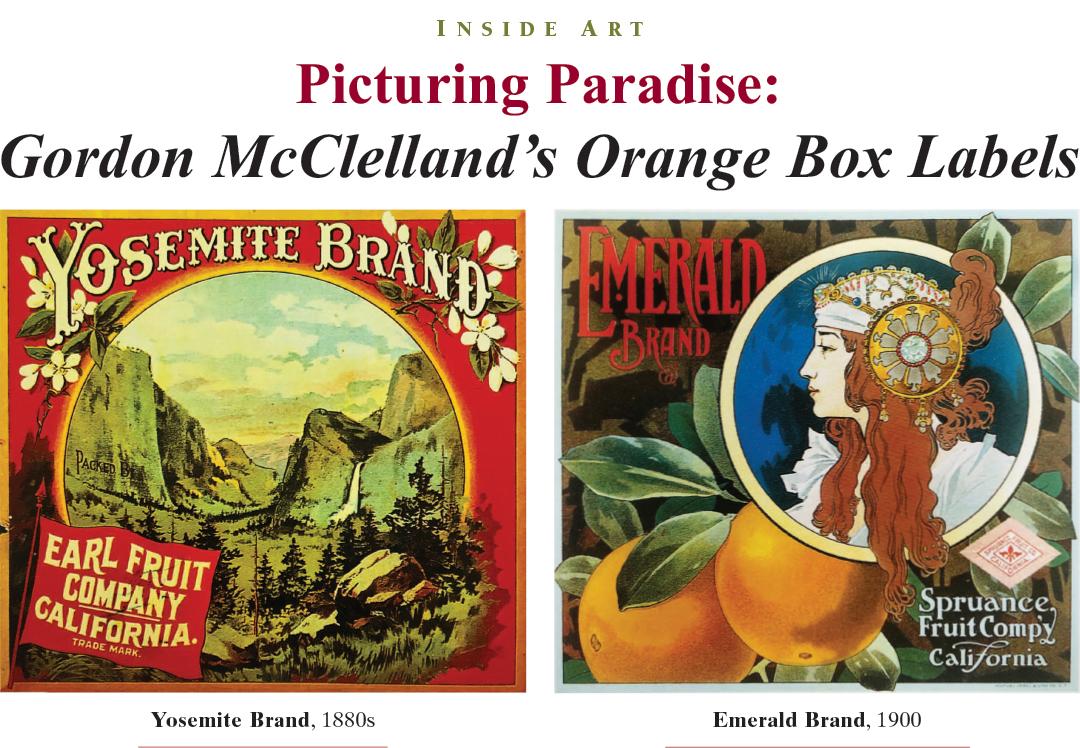

These colorful, eye-catching labels are the focus of one of the current exhibitions at the Hilbert Museum of California Art at Chapman University. “Picturing Paradise: The Art of California Orange Box Labels” was curated by author and California art historian Gordon McClelland, who began collecting labels in the 1960s and was one of the earliest aficionados of the art form. The labels in the show are from his collection and that of fellow collector Tom Spellman. Many have never been seen in a museum or book before.

“These paper labels became standardized at about 11 inches by 10 inches, which fit the ends of the standard rectangular wooden shipping crates,” says McClelland. “Their purpose was to rapidly catch the attention of prospective customers.”

In the hands of a good artist and graphic designer, the orange box label became an elegant small poster, containing an easily understood and remembered message. “Specifically, this is an exhibition focused on the art and the artists who created the labels,” says McClelland. “No other exhibition we’ve done has spotlighted the artists. Usually, we’ve focused on the history of the labels.”

The artists who created the labels between 1885 and 1920 were trained in the last half of the 19th century, and almost all these early labels included Victorian-style design elements in their portrayals of flowers, orange groves, cowboys, Native Americans, animals, women and other subjects. “It was detailed, eye-catching representational art, on a par with the paintings of the era,” says McClelland.

These artists were also very aware of the great poster artists in Europe, such as Toulouse-Lautrec, Cheret, Steinlen and Mucha, and were influenced by their artistic styles, according to McClelland. “Many of these lithographic artists actually came to the U.S. from Europe, mostly from France, Germany and England.”

McClelland’s fascination with fruit crate labels began when he was 7 or 8 years old. He would spot them at the produce market and ask if he could have them. Later, as a teenager who made extra money by creating posters for rock groups in Orange County, he began studying and appreciating the graphics and lettering of the old fruit labels.

“Then, between ages 16 and 18, I drove everywhere in the U.S. collecting fruit and vegetable labels. I knew cardboard boxes had changed the game suddenly in 1955, and companies now printed directly on the boxes. All the old paper labels were either stockpiled and half-forgotten at packing houses, shipping companies or printing companies, or were in danger of being thrown out. I visited places where labels might be stored, and they would often just give me stacks of hundreds of them, or I’d buy them for a nominal fee.”

In the late 1960s, there was virtually no market for these beautiful old labels, but McClelland and a few dedicated collectors saw their intrinsic beauty and saved thousands of them from destruction. Along the way, he became friends with Jay T. Last and got to know him as a shy, very knowledgeable fellow label collector. Last was also a famed American physicist, co-creator of the first silicon circuit chip, and one of the pioneering founders of Silicon Valley.

Last and McClelland co-authored several books, including California Orange Box Labels and Fruit Box Labels, now sold at the Hilbert Museum. (Last died in 2021 at 92 and gifted his collection of more than 185,000 original paper lithographs, including more than 1,000 citrus labels, to the Huntington Library in San Marino.) McClelland took his labels on tour to Europe in the 1970s and 1980s, with shows at various arts centers and museums. “We discovered Europeans really loved and appreciated them as art,” he says.

Today, the crate labels have become very desirable and collectible, with some commanding high prices—and you can see why. Bold, historical designs like “Chapman’s Old Mission Brand” label on the inside front cover shared space with the Mucha-inspired “Emerald” brand, and the action packed “Bronco” brand, while “Orange Queen” celebrates romantic feminine beauty and “Yosemite” extolls the wonders of California. At the Hilbert exhibition, you’ll see these and dozens of others, and gain new understanding of the history and the artists who created this very California graphic art form.

- - - -

Gordon McClelland will lecture on the orange crate labels on Saturday, January 18 at 6 pm at the Hilbert Museum, 167 North Atchison St. Tickets $10, Tickets.Chapman.edu