In our current troubled era, beset by a worldwide pandemic, political unrest and environmental disasters, people seem to be turning to calming, often ancient and time-honored practices: meditation, yoga, various forms of spirituality. So, it seems timely that an acclaimed Orange artist is advocating a very old contemplative practice and art form: the collection and display of “viewing stones” or “scholar’s rocks.”

But a rock is just a rock, right? One might think so—but to ancient Chinese scholars and aristocrats, some unusual, beautiful or particularly evocative stones became objects of special appreciation and contemplation. They would carefully collect these unique stones and display them in their gardens, homes or workplaces for the purpose of aesthetic appreciation.

The practice spread from China to Japan and Korea over many centuries. It is still very popular in many Asian countries today, with a growing and significant following in the U.S.

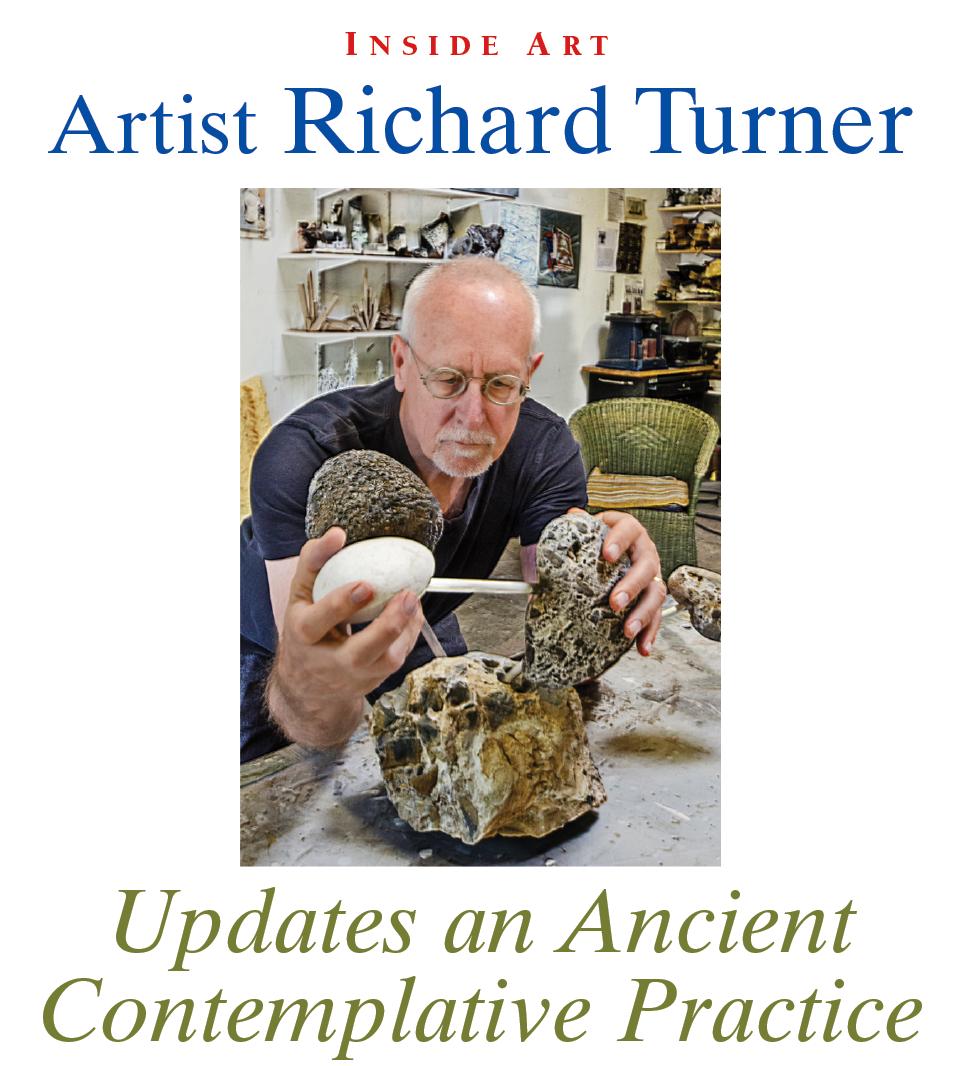

Richard Turner is an emeritus professor of art at Chapman University who taught studio art and Asian art history at the school for 41 years before his retirement in 2011. He also served as director of Chapman’s Guggenheim Gallery. Turner is lead author of a new book, Contemporary Viewing Stone Display, published this year by the Viewing Stone Association of North America.

Turner recalls how he first became aware of, then fascinated by, the concept of viewing stones. “I always loved to talk about Chinese and Japanese gardens in my Asian art history classes,” he says. “As I became more familiar with these gardens, I noticed that in some Chinese gardens there were sections of outdoor displays featuring strange and fascinating stones. I began to wonder if there was anything like them here in Southern California.”

He recounts how, at around the same time, he was invited to a meeting of a local bonsai club. “The bonsai master, whom I watched groom a tree, was also a master carver of bases for stones collected here in the U.S. He said something that tipped the balance for me between bonsai and stones. ‘Bonsai flourishes on attention; stones flourish on neglect.’ I thought, yes, that’s perfect for me!”

Chinese viewing stones are called “scholars’ rocks,” because initially it was scholars, poets and artists collecting them. “They put them on their desk or table so while they composed poetry, created a painting or a piece of calligraphy, they’d be in the presence of this stone that evoked a distant mountain peak, or a human or animal figure, or even a deity,” says Turner. “At a very elemental level, the stone could also be seen as an expression of the primal energy of the universe itself.”

Japan’s early culture was highly influenced by China. As travelers and collectors brought viewing stones from China to Japan, the practice became popular there, ultimately taking on a distinctly Japanese form. “The Japanese began to appreciate stones that reflected their own geology and tastes, as well as being influenced by existing Shinto practices,” Turner explains.

“The types of stones they collected in their practice—which is known there as suiseki—were more related to landscapes than to figures, and the way they displayed them was simpler in terms of the bases they would create. The bases for Chinese viewing stones were typically more elaborate, derived from the type of furniture that would be used to display a fine vase, for example. But in Japan they preferred a style of display that was quite simple and that highlighted the stone itself, so there wasn’t as much of a dialogue between the base and stone.”

The first viewing stone clubs in the U.S. date back to the post-WWII period and were primarily Japanese rather than Chinese, because of the large Japanese American population here. “Annual exhibitions by these early suiseki clubs soon attracted a wider group of people, and membership grew,” says Turner.

Turner’s own artwork is often informed by his interest in Chinese scholars’ rocks and Japanese suiseki. He has curated three exhibitions of viewing stones displayed alongside, and in an artistic dialogue with, contemporary work by sculptors, painters, ceramicists and photographers.

“Working with viewing stones offers the opportunity to build on a tradition that was centuries in the making. I see the evolution of viewing stone connoisseurship in China and later in Japan as an impetus to develop a distinctly contemporary practice grounded in regional geology and landscape that is responsive to 21st century art, politics and environmental issues.”

Turner has three goals with his book. “First, to give readers a sense of the long and fascinating history of stone appreciation in China, Japan, Korea and the U.S. Second, to encourage readers to make this tradition their own. The chapters on principles of display are intended to inspire creating viewing stone displays using materials readily available at Home Depot or Ikea.

“Third, we’d like our readers to consider that viewing stones can be understood as vehicles for thinking about our troubled relationship with the environment. In our current geological epoch, the Anthropocene, we humans are doing more to change the so-called natural world than wind, water, weather or any other element. We are responsible for climate change, and we are, therefore, a force of nature. We love to go to national parks and understand the healing nature of communion with the natural world. But we also need to acknowledge that we are mistreating our planet, exploiting and polluting it.”

Several of the contemporary viewing stone displays Turner includes in his section of the book suggest that urgent connection to human abuse of the planet’s environment. Traditional stone displays, especially in Japan, emphasize harmony and tranquility. But that’s only part of the story of our relationship to the Earth, says Turner.

Turner’s work featured on the inside front cover of this issue is intended by the artist to provoke political and social discourse. It features a specimen of Desert Rose, a form of selenite that crystallizes in petal-like formations, mounted vertically to evoke its similarity to an explosion flowering in the atmosphere. The shape of the stone is cloudlike, and the “petals” of the selenite have a roiling quality like the billowing cloud of an atomic blast.

“Atomic tests were frequently conducted in the deserts of New Mexico, Utah and California in the 20th century,” says Turner. “The above-ground nuclear tests conducted in Utah in 1953 were upwind of the site where the Holly-wood movie “The Conqueror” was being filmed. Of the 220 members of cast and crew of the film, 91 of them, including John Wayne, later died of cancer, leading to speculation that their deaths had been caused by exposure to radiation from the blasts,” says Turner.

The base from which the Desert Rose ascends is fashioned from a fragment of an inexpensive plaster statue of a Roman soldier. Pieces of the armor and the tunic are visible on the front of the base. “Taken together, the rising cloud of the explosion and the fragment of the fallen soldier could be seen as an acknowledgement of the abiding ubiquity of war. The Desert Rose could also be read as clusters of relentlessly dividing cancer cells and the Roman soldier as a symbol for victims of the disease.”

For more information about Richard Turner’s art, curatorial projects and scholarship, including his work with viewing stones, visit his website: www.turnerprojects.com

The new book Contemporary Viewing Stone Display by Richard Turner, Thomas S. Elias and Paul A. Harris, is available on the homepage (Bookstore section) of the Viewing Stone Association of North America website: http://vsana.org