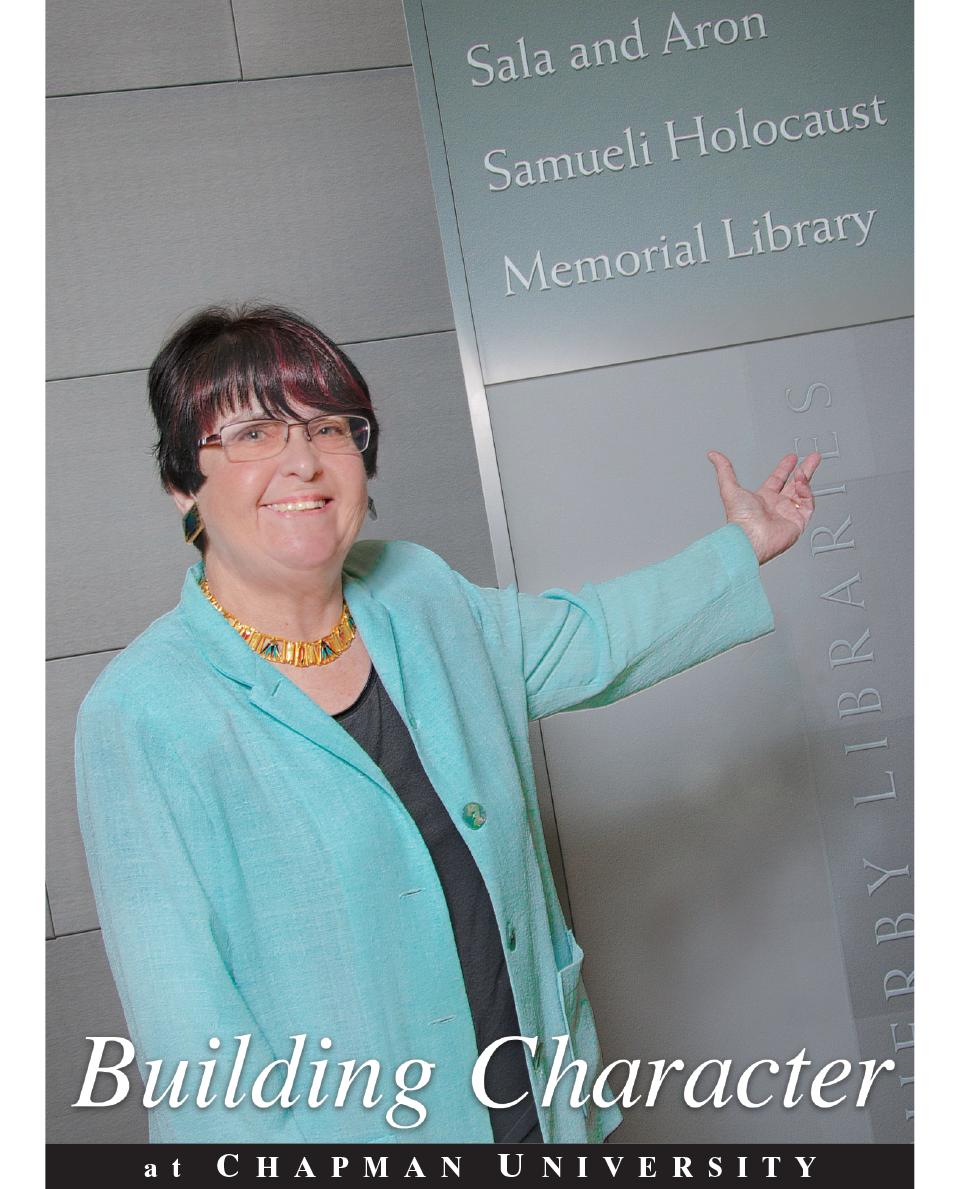

Dr. Marilyn Harran

In 1976, during her first year teaching at Barnard College, Columbia University, Marilyn Harran spent many hours in her office writing her dissertation. As she worked late into the night, the school’s custodian, a quiet, Polish man with a heavy accent, checked on her periodically. On one of those nights, he asked her to view something that would plant the seeds for her eventual work at Chapman University.

“Out of politeness, I agreed to look at some drawings that his wife had done,” says Harran, who earned an M.A. and Ph.D. from Stanford University. “He handed me the drawings, which were done on brown paper in charcoal, and I was speechless. His wife was a survivor of the Auschwitz death camp, and the drawings were of the stacks of bodies and furnace chimneys she saw when she first arrived in the concentration camp.”

The sketches, which indelibly etched themselves in Harran’s mind, left her at a loss as to what to say or do. Christian in background and the only child of Depression-era parents, Harran had only recently read her first book about the Holocaust, which she had chosen for an introductory religion course she was to teach. Night, by 1986 Nobel Peace Prize recipient Elie Wiesel, recounted the author’s experience in Auschwitz and Buchenwald as a teenager, and the drawings Harran held in her hands paralleled Wiesel’s portrayal of one of the darkest times in history.

“When I first saw the drawings, I thought that I had no place and basis by which to know how to respond to them, and in some ways I still don’t,” says Chapman’s Stern Chair in Holocaust Education and founding Director of the University’s Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education. “It’s hard for any of us, and certainly for me as someone who is not Jewish to reflect on the fact that educated people constructed a hierarchy of human beings in which some people were not even considered human. These lawyers, engineers and physicians were adept at creating the rationale to support their classification of people as of greater or lesser value.”

As Harran taught at Barnard over the next nine years, the drawings and the unimaginable horrors they represented continued to resound in the halls of her mind. Though she intended to stay at Barnard, and had turned down other job offers, including one from Harvard Divinity School, after experiencing a second mugging on the streets of New York City and because of some unsettling changes at the college, in 1985 she responded to an ad for a position at then Chapman College and traveled to the school for an interview.

“I flew out to Southern California in February when everyone in New York thinks it’s never going to be spring,” she recalls. “When I saw the sunken lawn, I thought it was the most beautiful green I had ever seen.” Harran interviewed with the college’s president at the time, G. T. (Buck) Smith, who told her that Chapman was a place where she could truly make a difference and then hired her as an associate professor of Religious Studies. Shortly after arriving, Harran worked with her colleagues to create an interdisciplinary course required of all freshmen on war, peace and justice that included a unit on the Holocaust. Students soon clamored for a full course on the subject.

“When none of my colleagues were interested in developing a course on the Holocaust, I decided to do so and tried to teach myself as much as I could, striving not to oversimplify what is complex and difficult history on many levels,” says Harran. The class struck a nerve and lead to more courses, and eventually in 1999, she was asked to collaborate on the 800-page book, The Holocaust Chronicle: A History in Words and Pictures. The book published in 2000, the same year that the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education opened and Harran became the Stern Chair in Holocaust Education. Not long after in 2005, the Sala and Aron Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library was dedicated.

Various events are held throughout the year through Chapman’s Holocaust program, including the “1939” club lecture series, which is an organization for Holocaust survivors and their descendants. Member’s stories were recently published in the February 2010 publication, Holocaust Survivors: The Indestructible Spirit, which is part of a photography and memoir project in which Chapman students interviewed survivors. Every March, the center also holds the Holocaust Art and Writing Contest, which is open to 7th through 12th graders. Students listen to and view oral testimonies from the survivors and then create responses with art, poetry or prose. One of the highlights of the contest is that students chosen by their teachers to participate in the contest have a chance to meet the survivors, notes Jessica MyLymuk, assistant director of the Rodgers Center. “The survivors love the event, which makes them feel very special and deeply valued,” she says. “Students have an opportunity to sit and talk with them during the reception, which lasts two hours.”

To Harran, connecting survivors and the younger generation is key. “Anyone who was not there can’t describe the experience, but I believe that it is extremely important that we try our utmost to guard the memories,” she says. “As we move into a time in which no people will be left to speak firsthand about what they experienced, more and more of the burden falls on us to prepare a new generation of knowledgeable guardians of the past. My role is to pique students’ interest to learn and to encourage them to take seriously the responsibility of knowledge.”

Jennifer Keene, Professor and Chair of Chapman’s History Department thinks that Harran has accomplished her goal. “Chapman has one of the most vibrant and unique Holocaust programs in the nation because it builds human connections among various generations,” says Keene. “Student after student has told me how they waited for years to get into Marilyn’s classes, and once in them they had to work harder than they ever worked before, yet they were grateful for the experience.”

Recent graduate Liane Burns is one such student. After taking a course from Harran during her freshman year, the dance major declared a minor in Holocaust History, even though she’s not Jewish, and this fall she will be studying dance in Jerusalem and taking graduate courses in Jewish and Israeli Studies from Hebrew University.

“Dr. Harran is one of the hardest professors at Chapman University, but that’s because she deeply cares about her students and their education,” says Burns. “The lessons I learned from Dr. Harran will continue to affect me throughout my future years. I was always interested in WWII and the Holocaust, but it was Dr. Harran's enthusiasm, passion and her belief that the Holocaust was not only an offense against some people, but an offense to all of humanity that really encouraged and moved me to study the Holocaust further. Dr. Harran introduced me to many survivors, including Elie Wiesel, who spoke to our class on two occasions. The memories of these men and women are unimaginable to me, but their trust and belief in the power of education has impacted me forever.”

The Sala and Aron Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library

Dedicated in April 2005, the Sala and Aron Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library located on the fourth floor of Chapman’s Leatherby Libraries, offers visitors the chance to learn the stories of survivors through words, pictures and artifacts. When you enter the library, you see a display of the full lives Jews led in Europe prior to the Holocaust; as you move through the exhibits, they chronicle the establishment of Jewish ghettos throughout Poland at the beginning of the war, the widespread internment in the death camps and the long-hoped-for Liberation.

Various displays highlight the stories of survivors, such as German-born, well-known actor Curt Lowens, who appeared in the movie “Angels & Demons.” Lowens and his parents were among the fortunate few to gain visas to the United States, and they were ready to board their ship in Rotterdam, the Netherlands when Germany invaded. The Lowens were taken to Westerbrook, the transit camp from which trains were sent to Auschwitz, but were able to gain their release and went underground. Lowens then joined the Dutch resistance and helped save two downed American airmen and more than 100 Jewish children in hiding.

The displays also pay homage to individuals who did not sit idly by, such as Oskar Schindler, of the famed “Schindler’s List” film, who saved 1,200 Jews by employing them in his factory.

The Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library is open Monday through Thursday from 9 am to 4 pm and Friday from 9 am to 3 pm. Group tours are available. Call (714) 628-7377 for more information.